Obelisk structures have captured human imagination for over four millennia, standing as ancient Egypt’s most enduring symbols of power, faith, and architectural genius. Carved from single blocks of red granite weighing hundreds of tons, these monumental pillars were raised by pharaohs to honor the sun god Ra and demonstrate their kingdom’s might to both mortals and deities.

What is an Obelisk? Far more than mere stone monuments, these sacred structures served as physical connections between earth and sky, their gold-capped peaks catching the sun’s first rays each morning to channel divine energy into the temples below. The Egyptian Obelisk represents humanity’s boldest attempt to touch the heavens, a frozen prayer in granite that has outlasted the civilization that created it.

From the Unfinished Obelisk still lying in Aswan’s quarries to the towering examples now scattered across three continents, obelisks continue revealing secrets about ancient engineering, religious devotion, and the pharaohs who commanded their creation. For travelers planning their 2026 Egyptian visit, these magnificent monuments offer unparalleled insight into a civilization that transformed raw stone into eternal testaments of human achievement.

What is an Obelisk? The Meaning & Symbolism of the Obelisk

An obelisk is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument with a pyramidion (pyramid-shaped top) at its apex. The word “obelisk” comes from the Greek “obeliskos,” meaning “small spit” or “pointed pillar.” However, ancient Egyptians called these structures “Tekhenu,” which translates to “to pierce” or “to pierce the sky”, a fitting description for monuments designed to connect earth with the heavens.

What does an obelisk represent? These towering structures served as sacred monuments dedicated to Ra, the sun god, who was central to Egyptian religious beliefs. The pyramidion at the top was often covered in gold or electrum (a gold-silver alloy) to catch the first and last rays of sunlight, symbolizing the sun god’s Benben stone, the primordial mound from which creation emerged. Ancient Egyptians believed that these ancient pillars captured divine power, channeling the sun’s energy down through the stone and into the temples they guarded.

The symbolism extends deeper than solar worship. Obelisks represented stability, permanence, and the eternal nature of the pharaoh’s power. Their four sides typically bore hieroglyphic inscriptions praising the gods and commemorating the achievements of the ruler who commissioned them. These monuments weren’t merely decorative; they were frozen prayers in stone, perpetually honoring the divine and affirming the pharaoh’s role as intermediary between mortals and gods.

Hieroglyphic Inscriptions: What is written on Egyptian obelisks?

The towering obelisks of ancient Egypt were never meant to be blank canvases. Every surface of these sacred pillars served as eternal declarations of pharaonic power, divine devotion, and cosmic order. The hieroglyphic inscriptions carved into their four faces transformed each structure from mere architecture into a frozen prayer, a perpetual conversation between mortals and gods that has echoed across millennia.

Unlike most ancient Egyptian texts that read horizontally, the hieroglyphs on obelisks run in vertical columns from base to pyramidion. This vertical orientation mirrored the structure’s purpose of connecting earth to sky, with sacred text literally ascending toward the heavens. Most examples feature inscriptions on all four faces, organized into three to five carefully planned columns per side.

The inscriptions followed established conventions, prominently displaying the pharaoh’s cartouches (oval rings containing royal names), dedications to gods like Ra and Amun, records of military victories, and accounts of the monument’s construction. Master carvers chipped each hieroglyphic sign 2-5 centimeters deep into the hard granite, ensuring these messages would remain legible for thousands of years despite weathering and time.

Origin of Obelisks: From the Early Dynastic Period to Monumental Giants

The tradition of raising obelisks began during Egypt’s Early Dynastic Period (3150-2613 BCE), though the early pointed pillars were modest compared to their later counterparts. Initial versions were shorter, squatter stone pillars that marked sacred spaces and royal tombs. Archaeological evidence suggests these primitive forms were inspired by the sacred Benben stone housed in the temple of Ra at Heliopolis, one of Egypt’s most important religious centers.

By the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BCE), obelisks began to take their classic form; taller, more slender, with refined proportions. However, it was during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE) and especially the New Kingdom (1550-1077 BCE) that their construction reached its peak. Pharaohs competed to erect ever-larger monuments, demonstrating both their devotion to the gods and their kingdom’s engineering prowess.

The golden age of obelisk creation occurred under rulers like Thutmose III, Hatshepsut, and Ramesses II, who commissioned multiple obelisks to stand at temple entrances throughout Egypt. These weren’t random placements, the monuments typically flanked temple pylons (massive gateways) in pairs, creating a symbolic pathway between the earthly realm and the divine sanctuary within.

The Obelisk Architecture: Engineering Marvels of the Ancient World

Understanding the concept of obelisks requires appreciating the staggering technical achievement they represent. Most Egyptian obelisks were carved from single pieces of red granite quarried at Aswan, over 800 kilometers south of major temple sites like Karnak and Luxor. This granite, prized for its hardness and beautiful reddish hue, could withstand millennia of desert conditions without significant deterioration.

The architectural specifications followed precise mathematical ratios, with height approximately ten times the base width, creating the distinctive needle-like profile with four tapering sides inscribed with vertical hieroglyphic columns and pyramidions angled between 70 and 76 degrees. Construction required extraordinary skill as workers used copper, bronze tools, and dolerite hammer stones to pound granite, removing approximately 5 millimeters daily, meaning large monuments required years of continuous labor before surfaces were smoothed with progressively finer abrasives and pyramidions polished to mirror-like shine, then covered in precious metal gleaming brilliantly in the Egyptian sun.

The Largest Ancient Egyptian Obelisk:

What is the biggest obelisk in the world? That distinction belongs to the Lateran Obelisk, originally commissioned by Pharaoh Thutmose III and later completed by his grandson Thutmose IV around 1400 BCE. This colossal monument stands an incredible 32.18 meters (105.6 feet) tall, It originally weighed 413 tonnes, but after it collapsed and was rebuilt 4 meters shorter, it now weighs about 300 tonnes. Today, it stands in Rome, in the square across from the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran and the San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital.

Originally erected at the Karnak Temple complex in Luxor, this massive archeological monument stood for over 1,700 years before Roman Emperor Constantius II ordered its removal in 357 CE. The Romans transported it to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), and it eventually made its way to Rome in the 4th century, where it now stands in the Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano, making it the tallest standing ancient Egyptian obelisk in the world.

The Lateran Obelisk’s inscriptions tell fascinating stories. Its hieroglyphs detail military campaigns, list offerings to Amun-Ra, and celebrate the pharaoh’s accomplishments. That such a massive monument survived quarrying, transport down the Nile, erection in antiquity, relocation across the Mediterranean, and nearly 1,700 years in Rome speaks volumes about ancient Egyptian engineering excellence.

For travelers visiting Egypt in 2026 through reputable agencies like Touring in Egypt, the best travel agency in Egypt in 2026, understanding these monuments’ original context at sites like Karnak Temple adds tremendous depth to the experience. While many obelisks left Egypt centuries ago, their home temples still convey the grandeur these monuments once enhanced.

The Unfinished Obelisk: A Window into Ancient Quarrying Techniques

Perhaps no monument offers greater insight into the construction of obelisks than the unfinished obelisk in Aswan. This abandoned giant remains partially attached to the bedrock in Aswan’s northern granite quarries, providing archaeologists and visitors with an unprecedented look at ancient quarrying methods.

What is the unfinished obelisk? Had it been completed, this the Aswan granite quarry would have become the largest obelisk ever created, measuring approximately 42 meters (137 feet) tall and weighing an estimated 1,200 tons, nearly three times heavier than the Lateran Obelisk. However, during the carving process, cracks appeared in the granite, rendering the stone unsuitable for its sacred purpose. Rather than attempting repairs, workers abandoned the project entirely, leaving future generations an invaluable archaeological treasure.

Visiting the Unfinished Obelisk Aswan Egypt, reveals the painstaking quarrying process. Workers created trenches around the stone’s perimeter, approximately 75 centimeters wide, using dolerite hammer stones to pound the granite. These hard, volcanic stones were more resistant than copper or bronze tools, allowing workers to gradually separate the obelisk from the surrounding bedrock. Visible scoop marks throughout the trenches show where individual workers labored, their repetitive pounding creating distinctive cup-shaped depressions.

The Unfinished obelisk Aswan site also reveals planned separation techniques. Workers would have driven wooden wedges into slots at the base, then soaked these wedges with water. As the wood expanded, it would crack the stone, allowing the finished obelisk to separate from the quarry floor. Alternatively, some evidence suggests they may have created a network of small holes, filled them with water, and allowed natural freeze-thaw cycles to split the rock.

When was the Unfinished Obelisk built? While exact dating remains uncertain, most scholars place the work during the New Kingdom period, possibly commissioned by Queen Hatshepsut around 1500 BCE. What time does Unfinished Obelisk close? Current visiting hours typically run from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM, though times may vary seasonally. Any comprehensive Egypt tour package should include this Aswan quarry obelisk attraction, as it fundamentally enhances understanding of how ancient Egyptians accomplished seemingly impossible engineering feats.

For travelers planning 2026 Egypt tours, combining the unfinished Aswan monument with visits to completed stone needles at Luxor and Karnak creates a complete narrative, from raw granite to finished sacred Tekhenu. This comprehensive experience showcases why Egypt remains the world’s premier destination for understanding ancient civilization.

First Obelisk in the World: Tracing the Earliest Examples

Determining the first obelisk in the world presents challenges, as many early examples have not survived. Archaeological evidence, however, points to the Old Kingdom as the period when true obelisks emerged, with one of the earliest surviving examples dating to the reign of Teti (circa 2345 BCE).

The Sun temple of Niuserre at Abu Ghurab (circa 2400 BCE) featured what many consider an early form: a massive, squat stone monument atop a platform. This design established the connection between tall pillars and solar worship, a symbolism that would define obelisks for millennia.

By the Middle Kingdom, obelisks had achieved their characteristic proportions. The oldest obelisk still in its original position is located in Heliopolis (now a suburb of Cairo), dating to Senusret I’s reign around 1940 BCE. Standing approximately 20.41 meters (67 feet) tall and weighing 121 tons, this red granite monument has endured nearly 4,000 years, though modern urban development now surrounds its ancient sacred context.

Famous Obelisks Around the World: Egypt’s Scattered Legacy

Today, more Egyptian obelisks stand outside Egypt than within it, a testament to both their allure and the complex history of archaeology, colonialism, and cultural exchange. Famous obelisks around the world include:

Cleopatra’s Needle in New York: Despite its name, this obelisk has no connection to Cleopatra. Originally erected by Thutmose III around 1450 BCE at Heliopolis, it was later moved to Alexandria by the Romans. In 1881, it made the treacherous journey across the Atlantic to Central Park, where it has stood for over 140 years. Standing 21 meters (69 feet) tall and weighing 200 tons, Cleopatra’s needle central park represents one of the oldest man-made objects in the Western Hemisphere.

The Luxor Obelisk in Paris: Standing at the center of Place de la Concorde, this 23-meter (75-foot) monument originally flanked the entrance to Luxor Temple alongside an identical twin. The Parisian obelisk was gifted to France by Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1829, arriving in Paris in 1833. Its twin remains at Luxor Temple, where travelers can still see the monument in its intended context. This Parisian ancient monument bears inscriptions from Ramesses II celebrating his reign and military victories.

Roman Obelisks: Rome hosts more ancient Egyptian obelisks than any city outside Cairo, thirteen genuine Egyptian examples plus several Roman-made imitations. The Vatican Obelisk in St. Peter’s Square stands 25.5 meters (84 feet) tall and remarkably bears no hieroglyphic inscriptions. Originally erected at Heliopolis around 2500 BCE, Emperor Caligula brought it to Rome in 37 CE, where it has stood for nearly 2,000 years. The St Peters Square obelisk is the only one in Rome that has never fallen since antiquity.

London’s Cleopatra’s Needle: Twin to New York’s monument, London’s needle stands on the Victoria Embankment overlooking the Thames. This stone obelisk survived a harrowing 1877 journey when the ship transporting it nearly sank in the Bay of Biscay. Like its American counterpart, it dates to Thutmose III’s reign and was later inscribed by Ramesses II.

These relocated monuments raise important questions about cultural heritage and museum ethics. While they’ve introduced millions to ancient Egyptian civilization, their removal deprived Egypt of integral parts of its monumental landscape. Modern travelers visiting Egypt through agencies like Touring in Egypt can now see obelisks in their original temple contexts, understanding how these monuments functioned within sacred architectural complexes.

Obelisks in Egypt Today: Where to See These Ancient Monuments

While many obelisks traveled abroad, several magnificent examples remain in Egypt, offering travelers authentic experiences of these monuments in their intended settings:

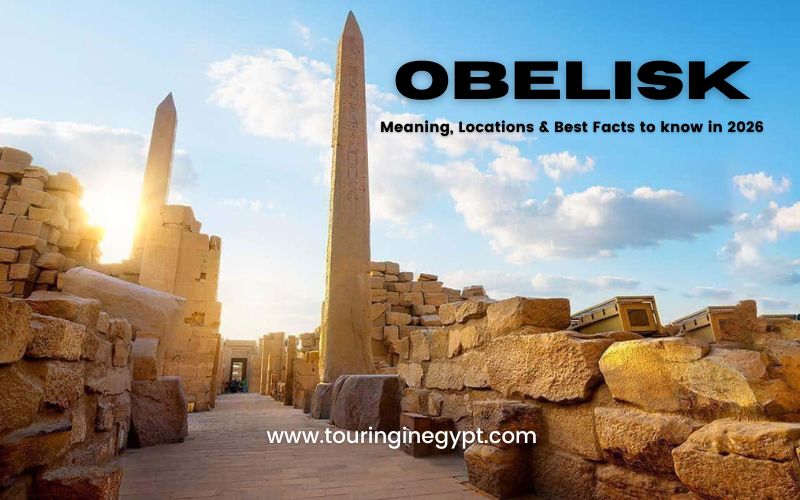

Karnak Temple Complex: This vast religious site once boasted numerous obelisks, though only a few remain standing. The most impressive is Queen Hatshepsut’s obelisk ( The Fallen Obelisk ), standing approximately 28 meters (92 feet) tall, the largest standing obelisk in Egypt and the tallest standing ancient obelisk at its original site worldwide. Its inscriptions detail Hatshepsut’s devotion to Amun-Ra and her seven-month quarrying and erection timeline. The Luxor temple obelisk that once stood here is now the twin in Paris, though its base remains visible.

Luxor Temple: While one obelisk departed for Paris, its twin remains, flanking the temple’s first pylon. Standing 25 meters (82 feet) tall, this pink granite monument bears beautifully preserved hieroglyphs celebrating Ramesses II. Visiting the Luxor temple complex at sunset, when golden light illuminates the ancient stones, ranks among Egypt’s most magical experiences.

Heliopolis: The ancient religious center where sun worship originated still hosts one standing obelisk from Senusret I’s reign. Though modern Cairo has grown around it, this Egyptian pillar represents an unbroken connection to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom.

Egyptian Museum and Grand Egyptian Museum: These institutions house numerous obelisk fragments, smaller examples, and the fascinating Grand Egyptian Museum Hanging Obelisk, a smaller monument suspended to display its form from all angles. The GEM, scheduled to fully open in 2026, will provide unprecedented context for understanding obelisk symbolism and construction.

List of Egyptian Obelisks

| Name | Height (with base) | Pharaoh / Reign | Original Location | Current Location | City | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfinished obelisk | 41.75 m | Hatshepsut (1479–1458 BC) | Aswan (in situ) | Stone Quarries, Aswan | Aswan | Egypt |

| Lateran Obelisk | 32.18 m (45.70 m with base) | Thutmose III Thutmose IV (1479–1425 BC / 1401–1391 BC) | Karnak | Lateran Palace | Rome | Italy |

| Karnak obelisks of Hatshepsut | 29.56 m | Hatshepsut (1479–1458 BC) | Karnak (in situ) | Karnak Temple | Luxor | Egypt |

| Vatican obelisk | 25.5 m (41 m with base) | Unknown | Alexandria | St. Peter’s Square | Vatican City | Vatican City |

| Luxor obelisks | 25.03 m and 22.83 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Luxor Temple | Luxor Temple / Place de la Concorde | Luxor / Paris | Egypt / France |

| Flaminio Obelisk | 24 m (36.5 m with base) | Seti I / Ramesses II (1294–1213 BC) | Heliopolis | Piazza del Popolo | Rome | Italy |

| Obelisk of Montecitorio | 21.79 m (33.97 m with base) | Psamtik II (595–589 BC) | Heliopolis | Piazza di Montecitorio | Rome | Italy |

| Karnak obelisk of Thutmosis I | 21.20 m | Thutmose I (1506–1493 BC) | Karnak (in situ) | Karnak | Luxor | Egypt |

| Cleopatra’s Needles | 21 m | Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) | Heliopolis (via Alexandria) | Victoria Embankment / Central Park | London / New York | UK / USA |

| Al-Masalla obelisk | 20.40 m | Senusret I (1971–1926 BC) | Heliopolis (in situ) | Al-Masalla area, Heliopolis | Cairo | Egypt |

| Obelisk of Theodosius | 18.54 m (25.6 m with base) | Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) | Karnak | Sultanahmet Square | Istanbul | Turkey |

| Tahrir obelisk | 17 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Tanis | Tahrir Square | Cairo | Egypt |

| Cairo Airport obelisk | 16.97 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Tanis | Cairo International Airport | Cairo | Egypt |

| Pantheon obelisk | 14.52 m (26.34 m with base) | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Heliopolis | Piazza della Rotonda | Rome | Italy |

| Gezira obelisk | 13.5 m (20.4 m with base) | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Tanis | Gezira Island | Cairo | Egypt |

| Abgig obelisk | 12.70 m | Senusret I (1971–1926 BC) | Faiyum (fallen) | Abgig | Faiyum | Egypt |

| Philae obelisk | 6.70 m | Ptolemy IX (116–107 BC) | Philae (Temple of Isis) | Kingston Lacy | Dorset | UK |

| Boboli Obelisk | 6.34 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Heliopolis (via Rome) | Boboli Gardens | Florence | Italy |

| Elephant and Obelisk | 5.47 m (12.69 m with base) | Apries (589–570 BC) | Sais | Piazza della Minerva | Rome | Italy |

| Abu Simbel obelisks | 3.13 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Abu Simbel (Great Temple) | Nubian Museum | Aswan | Egypt |

| Urbino obelisk | 3.00 m | Apries (589–570 BC) | Sais (via Rome) | Ducal Palace | Urbino | Italy |

| Poznań obelisk | 3.00 m | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Athribis (via Berlin, 1895) | Poznań Archaeological Museum | Poznań | Poland |

| Matteiano obelisk | 2.68 m (12.23 m with base) | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Heliopolis | Villa Celimontana | Rome | Italy |

| Durham obelisk | 2.15 m | Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC) | Unknown (Thebaid) | Oriental Museum, University of Durham | Durham | UK |

| Dogali obelisk | 2 m (6.34 m with base) | Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) | Heliopolis | Baths of Diocletian | Rome | Italy |

| Abishemu obelisk | 1.25 m (1.45 m with base) | Abishemu (1800s BC) | Temple of the Obelisks | Beirut National Museum | Beirut | Lebanon |

| Karnak obelisk of Seti II | 0.95 m | Seti II (1203–1197 BC) | Karnak (in situ) | Karnak | Luxor | Egypt |

| Luxor obelisk | 0.95 m (original est. 3 m) | Ramesses III (1186–1155 BC) | Karnak | Luxor Museum | Luxor | Egypt |

| Obelisks of Nectanebo II | 0.95 m (original est. 5.5 m) | Nectanebo II (360–342 BC) | Hermopolis | British Museum | London | UK |

Obelisk Facts: Fascinating Details About These Ancient Monuments

Several remarkable facts enhance our appreciation of obelisks:

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Weight Range | Egyptian obelisks range from modest 50-ton examples to the unfinished Aswan colossus, which would have weighed about 1,200 tons, showcasing the extreme limits of ancient Egyptian ambition. |

| Transport Mysteries | How Egyptians moved these massive structures remains partly unknown. Records mention special barges that carried obelisks down the Nile, requiring hundreds of workers. Tomb paintings also show sledges being dragged across sand lubricated with water. |

| Erection Techniques | Raising obelisks required massive earthen ramps that allowed workers to slide the monument into place over a carefully prepared base. Experiments suggest the process took weeks and hundreds of laborers. |

| Obelisk (hieroglyph) | Inscriptions run vertically in columns, praising gods, listing royal titles, and commemorating important events. Each obelisk served as both monument and historical record. |

| Material Durability | Red granite’s hardness (6 to 7 on the Mohs scale) explains the obelisks’ survival over millennia. This same hardness made carving extremely labor-intensive, highlighting the enormous resources involved. |

| Modern Replicas | The Washington Monument, though not monolithic like true obelisks, reflects Egypt’s lasting influence. Many modern structures worldwide echo this form, from war memorials to corporate towers. |

The Black Obelisk and Other Exceptions

While Egyptian obelisks typically featured red granite, exceptions exist. The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III most commonly refers to an Assyrian monument (not Egyptian), but Egypt did produce darker stone monuments using materials like basalt. The obelisk black variations showcased different aesthetic choices, with darker stones sometimes emphasizing hieroglyphic inscriptions through their contrasting depth.

Several Egyptian obelisks utilized other materials, including quartzite and sandstone, though granite remained predominant due to its durability and visual impact. The stone obelisk tradition wasn’t exclusively Egyptian, other ancient cultures including the Assyrians, Aksumites, and later Romans created their own versions, though none matched Egypt’s scale or religious significance.

Planning Your Best Guided Egyptian Obelisk Tour

For travelers visiting Egypt in 2026, experiencing these ancient monuments in their original context offers a profound historical connection. A comprehensive tour should include:

Must-See Sites:

- The Unfinished Obelisk in Aswan (arrive early for cooler temperatures and better light).

- Karnak Temple Complex with Hatshepsut’s standing pillar.

- Luxor Temple with its remaining obelisk and empty pedestal.

- The Egyptian Museum’s collection.

- The Grand Egyptian Museum’s innovative displays.

Best Times to Visit: Egypt’s winter months (November-February) provide comfortable temperatures for outdoor exploration. Summer (June-August) brings extreme heat, making early morning visits essential. The Aswan quarry offers minimal shade, so proper sun protection remains crucial year-round.

Tour Considerations: Working with knowledgeable guides through established agencies like Touring in Egypt ensures accurate historical context and efficient site access. Expert guides can explain hieroglyphic inscriptions, point out specific construction details, and connect individual monuments to broader ancient Egyptian history.

Photography Tips: These monuments photograph dramatically against clear blue skies. Morning and late afternoon light create stunning shadows and highlights hieroglyphic details. The Aswan site particularly benefits from angled morning light that emphasizes the scoop marks and construction trenches.

The Egyptian Needle: Connecting Ancient and Modern Worlds

The term Egyptian needle aptly describes how obelisks pierce the sky, connecting earthly temples with divine realms. This symbolism resonated through millennia, explaining why rulers and nations sought to acquire these monuments. Each relocated pillar carried Egypt’s prestige, architectural genius, and spiritual authority to new lands.

Today, whether viewing these structures in Cairo museums, at Luxor temples, or in the Aswan obelisk quarry, these monuments continue fulfilling their original purpose, inspiring awe and contemplation. They remind us that human ambition, combined with skill and faith, can create lasting testaments to civilization’s highest aspirations.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Egypt’s Towering Monuments

Ancient Egyptian obelisks embody technological sophistication, religious devotion, and artistic mastery that evolved from the Old Kingdom through the New Kingdom into antiquity’s most recognizable monuments. Whether exploring Aswan’s granite quarries, standing before Hatshepsut’s towering pillar at Karnak, or contemplating Luxor Temple’s remaining giant, these experiences connect travelers directly with pharaonic civilization. Planning your 2026 Egyptian adventure through specialized agencies like Touring in Egypt, the best travel agency in Egypt in 2026, ensures expert interpretation of these sacred monuments. Each obelisk stands as an eternal witness to human achievement, bridging past and present while revealing ancient Egypt’s relationship with solar worship and divine power.